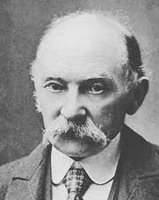

Thomas Hardy's

Thomas Hardy'sJude the Obscure

The institution of marriage was challenged throughout the Victorian period as well as the traditional roles of women as wives, mother and daughters. The "Woman Question," as it was called, was no less prominent an issue for debate than evolution or industrialism. "Discontent, whether godly or ungodly" as stated in The Norton Anthology of English Literature, "led to [a young woman's] open rebellion." At a time when women were to be valued for their "qualities considered to be especially characteristic of her sex,: tenderness of understanding, unworldliness and innocence, domestic affection, and in various degrees. submissiveness," Thomas Hardy's novel, Jude the Obscure, examines the institution of marriage and emerging modern views of Victorian English society.

Though I have enjoyed most of Thomas Hardy's works, I found myself becoming increasingly irritated with the character of Jude who comes across as a whining, gullible and weak man who keeps making the same stupid mistakes over and over again in his life. Much of the grief that he brings upon himself is avoidable by merely using his brain. Jude's circumstances are partly the fault of the society in which he lives, however he, himself is responsible for much of how events in his life unfold because basically, Jude has a defeatest attitude and attracts negativity.

From Sparknotes:

Jude the Obscure focuses on the life of a country stonemason, Jude, and his love for his cousin Sue, a schoolteacher. From the beginning Jude knows that marriage is an ill-fated venture in his family, and he believes that his love for Sue curses him doubly, because they are both members of a cursed clan. While love could be identified as a central theme in the novel, it is the institution of marriage that is the work's central focus. Jude and Sue are unhappily married to other people, and then drawn by an inevitable bond that pulls them together. Their relationship is beset by tragedy, not only because of the family curse but also by society's reluctance to accept their marriage as legitimate.The horrifying murder-suicide of Jude's children is no doubt the climax of the book's action, and the other events of the novel rise in a crescendo to meet that one act. From there, Jude and Sue feel they have no recourse but to return to their previous, unhappy marriages and die within the confinement created by their youthful errors. They are drawn into an endless cycle of self-erected oppression and cannot break free. In a society unwilling to accept their rejection of convention, they are ostracized. Jude's son senses wrongdoing in his own conception and acts in a way that he thinks will help his parents and his siblings. The children are the victims of society's unwillingness to accept Jude and Sue as man and wife, and Sue's own feelings of shame from her divorce.Jude's initial failure to attend the university becomes less important as the novel progresses, but his obsession with Christminster remains. Christminster is the site of Jude's first encounters with Sue, the tragedy that dominates the book, and Jude's final moments and death. It acts upon Jude, Sue, and their family as a representation of the unattainable and dangerous things to which Jude aspires.