Doris Lessing

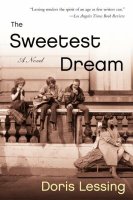

Doris LessingThe Sweetest Dream

From Publishers Weekly

In lieu of writing volume three of her autobiography ("because of possible hurt to vulnerable people"), the grand dame of English letters delves into the 1960s and beyond, where she left off in her second volume of memoirs, Walking in the Shade. The result is a shimmering, solidly wrought, deeply felt portrait of a divorced "earth" mother and her passel of teenage live-ins. Frances Lennox and her two adolescent sons, Andrew and Colin, and their motley friends have taken over the bottom floors of a rambling house in Hampstead, London. The house is owned by Frances's well-heeled German-born ex-mother-in-law, Julia, who tolerates Frances's slovenly presence out of guilt for past neglect and a shared aversion for Julia's son, Johnny Lennox, deadbeat dad and flamboyant, unregenerate Communist. Frances's first love is the theater, but she must support "the kids," and so she works as a journalist for a left-wing newspaper. Over the roiling years that begin with news of President Kennedy's assassination, a mutable assortment of young habituEs gather around Frances's kitchen table, and Comrade Johnny makes cameo appearances, ever espousing Marxist propaganda to the rapt young dropouts. Johnny is a brilliantly galling character, who pushes both Julia and Frances to the brink of despair (and true affection for each other). Lessing clearly relishes the recalcitrant '60s, yet she follows her characters through the women's movement of the '70s and a lengthy final digression in '90s Africa. Lessing's sage, level gaze is everywhere brought to bear, though she occasionally falls into clucking, I-told-you-so hindsight, especially on the subject of the failed Communist dream. While the last section lacks the intimate presence of long-suffering Frances, the novel is weightily molded by Lessing's rich life experience and comes to a momentous conclusion.

While I am a huge fan of Lessing's writing and did my Master's thesis on Lessing, for some reason this novel irritated me. One thing I found particularily annoying was whenever problems arose in the "family" or whenever there were things to discuss, Frances would head for the refrigerator and pull out food and make a huge meal no matter what time it was. It was as if food would "fix" any problem. Or maybe it was the way that Frances "martyred" herself for these punk kids, several of whom were ungrateful shitheads. It is also irritating the way she overuses the term "kids" for the young people she harbors. Most of them aren't "kids", they are hoodlums who take advantage of her. Frances has a martyr complex which leads her to tolerate jerks who turned around and betrayed her in horrendously destructive, cruel, and selfish ways, and I found myself frustrated with Frances for not having thrown them out. Especially the bastard of an ex-husband Johnny who she lets waltz into her house unannounced at any time.Now that I have these things off my chest, I can now go on to the good points about the novel.

Lessing is hard on all the ideologies that are touched upon through the plot: she goes after communists, hippies, feminists, the internationalist development elite, journalists, and even Third World leaders. In other words, there are no simple answers; instead, the questions just get tougher. While there is a lot of humor in this, it is very dense, a kind of reverse history of idealism, showcasing the self-serving egotism that underlies the motives of virtually all the characters. What is amazing is how well it succeeds in bringing these ideas to life through the characters, though I found the second half of the book, much of which takes place in Africa, less strong than the first half.

I don't feel this is Lessing's best work. It was too short of a novel for such complex problems and ideologies she was attempting to examine.

No comments:

Post a Comment